JBC: What bacteria can teach us about combating atrazine contamination

Atrazine, a controversial herbicide introduced to agriculture in the 1950s, has been banned in the European Union but is used widely in the United States and Australia. In the decades that atrazine has been accumulating in agricultural fields, some bacteria in those soils have evolved the ability to take advantage of this nitrogen-rich compound, metabolizing it and using it to grow.

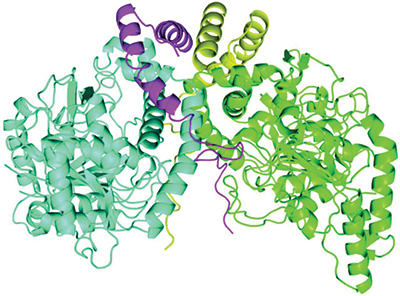

A newly described protein complex carries out a step in bacterial breakdown of the herbicide atrazine. The two AtzE molecules are in blue and green, and the two AtzG molecules are in yellow and magenta.Courtesy of Colin Scott/CSIRO

A newly described protein complex carries out a step in bacterial breakdown of the herbicide atrazine. The two AtzE molecules are in blue and green, and the two AtzG molecules are in yellow and magenta.Courtesy of Colin Scott/CSIRO

Researchers at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization of Australia, or , are interested in harnessing bacterial ability to degrade atrazine in order to remediate atrazine-polluted environments. In a published in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, a team from CSIRO and the Australian National University describe previously unknown proteins involved in atrazine degradation — and the insights these can give us into how bacteria evolve new abilities in response to chemicals synthesized by humans.

“Bacteria are really good at evolving to be able to exploit new nutrient sources, and they do this by adapting existing cellular machinery for novel functions,” said , leader of the Biocatalysis and Synthetic Biology Team at CSIRO, who oversaw the work.

Turning atrazine into a usable nitrogen source is a multistep process for bacteria, involving multiple enzymes. Before widespread atrazine pollution, each of these enzymes served different functions in bacterial cells. In atrazine-degrading bacteria, the genes encoding these enzymes are grouped on a section of DNA called a plasmid, which can be passed easily between bacteria, giving them a ready-made adaptation.

“Within 10 years from its original discovery (in the 1990s), genes from this pathway were found (in bacteria) on pretty much every continent except Antarctica,” Scott said.

In other words, as atrazine use spread across the globe, so did the bacterial ability to metabolize it.

Whereas the enzymes involved in several of these steps have been described thoroughly, the structure of one of them, called AztE, was still unknown. AztE is crucial for converting cyanuric acid — an intermediate step in the atrazine degradation process — into ammonia.

, a Ph.D. student in Scott’s lab, led the effort to purify this protein. When the team examined the protein, it found something surprising: another very small protein, the existence of which had not been predicted from the bacterium’s genome sequence, forming a complex with AztE. This new protein, which the team named AztG, seemed to be necessary to stabilize the structure of AztE.

Together, the structure of AztE and AztG resembled a different bacterial protein complex — the transamidasome, which helps make bacterial transfer RNA. Thus, it appeared that proteins involved in the basic functions of the bacterial cell were retooled for the new atrazine pathway.

The transamidasome “is absolutely essential for bacteria in the way that they make their tRNAs,” Scott said. “It was somewhat surprising that our protein, which is involved in pesticide catabolism, was (similar) to this protein complex that’s used in central metabolism.”

The promise of synthetic biology is that humans can combine genes encoding different functions in an organism in creative ways. However, although it’s relatively simple to insert genes into new contexts, a newly constructed pathway is not guaranteed to work as intended. It’s therefore instructive to examine pathways like the atrazine degradation pathway, in which bacteria have successfully repurposed a series of unrelated genes to do something new.

“This (pathway) has come from other places and been cobbled together, but there must be some underlying rules and constraints about how to do that,” Scott said. “We don’t know at the moment what the design rules are for complex pathways in terms of their genetic architecture. What we want to do is to use the cyanuric acid pathway as a model to understand some of those design principles.”

Atrazine-degrading bacteria convert atrazine into nitrogenous compounds that plants potentially could use as fertilizer, but this poses its own problems: Nitrogen runoff into water causes algal blooms and animal die-offs. Thus, a key problem that CSIRO researchers are trying to solve is how to contain the reaction so that it occurs only where and how humans need it. One approach is to use targeted application of enzymes purified from these bacteria rather than the bacteria themselves.

“As a technology, we’ve gone out to the field and proven that (the enzymes) can work,” Scott said. “The next step is working with industry to try to implement some of these solutions.”

Enjoy reading ASBMB Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

ApoA1 reduce atherosclerotic plaques via cell death pathway

Researchers show that ApoA1, a key HDL protein, helps reduce plaque and necrotic core formation in atherosclerosis by modulating Bim-driven macrophage death. The findings reveal new insights into how ApoA1 protects against heart disease.

Omega-3 lowers inflammation, blood pressure in obese adults

A randomized study shows omega-3 supplements reduce proinflammatory chemokines and lower blood pressure in obese adults, furthering the understanding of how to modulate cardiovascular disease risk.

AI unlocks the hidden grammar of gene regulation

Using fruit flies and artificial intelligence, Julia Zeitlinger’s lab is decoding genome patterns — revealing how transcription factors and nucleosomes control gene expression, pushing biology toward faster, more precise discoveries.

Zebrafish model links low omega-3s to eye abnormalities

Researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz developed a zebrafish model to show that low maternal docosahexaenoic acid can disrupt embryo eye development and immune gene expression, offering a tool to study nutrition in neurodevelopment.

Top reviewers at ASBMB journals

Editors recognize the heavy-lifters and rising stars during Peer Review Week.

Teaching AI to listen

A computational medicine graduate student reflects on building natural language processing tools that extract meaning from messy clinical notes — transforming how we identify genetic risk while redefining what it means to listen in science.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)